https://api.follow.it/track-rss-story-click/v3/jGd80SoQARX-lNVAUO9iX2_63bikK-sP

Will 2026 be the year we detect life elsewhere in the universe? The odds seem against it, barring a spectacular find on Mars or an even more spectacular SETI detection that leaves no doubt of its nature. Otherwise, this new year will continue to see us refining large telescopes, working on next generation space observatories, and tuning up our methods for biosignature detection. All necessary work if we are to find life, but no guarantee of future success.

It is, let’s face it, frustrating for those of us with a science fictional bent to consider that all we have to go on is our own planet when it comes to life. We are sometimes reminded that an infinite number of lines can pass through a single point. And yes, it’s true that the raw materials of life seem plentiful in the cosmos, leading to the idea that living planets are everywhere. But we lack evidence. We have exactly that one datapoint – life as we know it on our own planet – and every theory, every line we run through it is guesswork.

I got interested enough in the line and the datapoint quote that I dug into its background. As far as I can find, Leonardo da Vinci wrote an early formulation of a mathematical truth that harks back to Euclid. In his notebooks, he says this:

“…the line has in itself neither matter nor substance and may rather be called an imaginary idea than a real object; and this being its nature it occupies no space. Therefore an infinite number of lines may be conceived of as intersecting each other at a point, which has no dimensions…”

It’s not the same argument, but close enough to intrigue me. I’ve just finished Jon Willis’ book The Pale Blue Data Point (University of Chicago Press, 2025), a study addressing precisely this issue. The title, of course, recalls the wonderful ‘pale blue dot’ photo taken from Voyager 1 in 1990. Here Earth itself is indeed a mere point, caught within a line of scattered light that is an artifact of the camera’s optics. How many lines can we draw through this point?

We’ve made interesting use of that datapoint in a unique flyby mission. In December, 1990 the Galileo spacecraft performed the first of two flybys of Earth as part of its strategy for reaching Jupiter. Carl Sagan and team used the flyby as a test case for detecting life and, indeed, technosignatures. Imaging cameras, a spectrometer and radio receivers examined our planet, recording temperatures and identifying the presence of water. Oxygen and methane turned up, evidence that something was replenishing the balance. The spacecraft’s plasma wave experiment detected narrow band emissions, strong signs of a technological, broadcasting civilization.

Image: The Pale Blue Dot is a photograph of Earth taken Feb. 14, 1990, by NASA’s Voyager 1 at a distance of 3.7 billion miles (6 billion kilometers) from the Sun. The image inspired the title of scientist Carl Sagan’s book, Pale Blue Dot: A Vision of the Human Future in Space, in which he wrote: “Look again at that dot. That’s here. That’s home. That’s us.” NASA/JPL-Caltech.

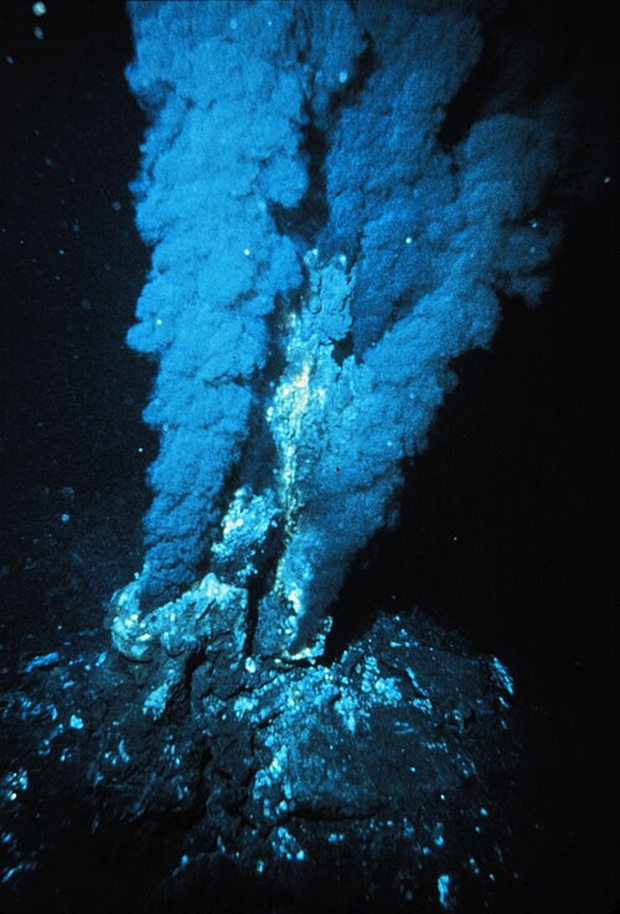

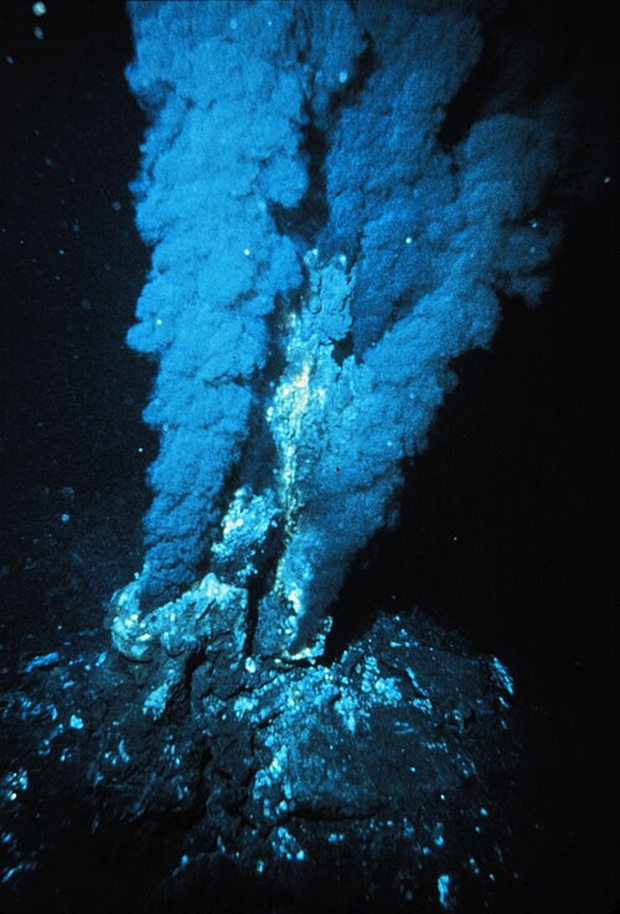

So that’s a use of Earth that comes from the outside looking in. Philosophically, we might be tempted to throw up our hands when it comes to applying knowledge of life on Earth to our expectations of what we’ll find elsewhere. But we have no other source, so we learn from experiments like this. What Willis wants to do is to look at the ways we can use facilities and discoveries here on Earth to make our suppositions as tenable as possible. To that end, he travels over the globe seeking out environs as diverse as the deep ocean’s black smokers, the meteorite littered sands of Morocco’s Sahara and Chile’s high desert.

It’s a lively read. You may remember Willis as the author of All These Worlds Are Yours: The Scientific Search for Alien Life (Yale University Press, 2016), a precursor volume of sorts that takes a deep look at the Solar System’s planets, speculating on what we may learn around stars other than our own. This volume complements the earlier work nicely, in emphasizing the rigor that is critical in approaching astrobiology with terrestrial analogies. It’s also a heartening work, because in the end the sense of life’s tenacity in all the environments Willis studies cannot help but make the reader optimistic.

Optimistic, that is, if you are a person who finds solace and even joy in the idea that humanity is not alone in the universe. I certainly share that sense, but some day we need to dig into philosophy a bit to talk about why we feel like this.

Willis, though, is not into philosophy, but rather tangible science. The deep ocean pointedly mirrors our thinking about Europa and the now familiar (though surprising in its time) discovery by the Galileo probe that this unusual moon contained an ocean. The environment off northwestern Canada, in a region known as the Juan Fuca Plate, could not appear more unearthly than what we may find at Europa if we ever get a probe somehow underneath the ice.

The Endeavor hydrothermal vent system in this area is one of Earth’s most dramatic, a region of giant tube worms and eyeless shrimp, among other striking adaptations. Vent fluids produce infrared radiation, an outcome that evolution developed to allow these shrimp a primitive form of navigation.

Image: A black smoker at the ocean floor. Will we find anything resembling this on moons like Europa? Credit: NOAA.

Here’s Willis reflecting on what he sees from the surface vessel Nautilus as it manages two remotely operated submersibles deep below. Unfolding on its computer screens is a bizarre vision of smoking ‘chimneys’ in a landscape he can only describe as ‘seemingly industrial.’ These towering structures, one of them 45 feet high, show the visual cues of powering life through geological heat and chemistry. Could a future ROV find something like this inside Europa?

It is interesting to note that the radiation produced by hydrothermal vents occurs at infrared wavelengths similar to those produced by cool, dim red dwarf stars such as Proxima Centauri, the closest star to our Sun and one that hosts its own Earth-sized rocky planet. Are there as yet any undiscovered terrestrial microbes at hydrothermal vents that have adapted the biochemistry of photosynthesis to exploit this abundant supply of infrared photons in the otherwise black abyss? Might such extreme terrestrial microbes offer an unexpected vision of life beyond the solar system?

The questions that vistas like this spawn are endless, but they give us a handle on possibilities we might not otherwise possess. After all, the first black smokers were discovered as recently as 1979. Before that, any hypothesized ocean on an icy Jovian moon would doubtless have been considered sterile. Willis goes on:

It is a far-out idea that remains speculation — the typical photon energy emitted from Proxima Centauri is five times greater than that emerging from a hydrothermal vent. However, the potential it offers us to imagine a truly alien photosynthesis operating under the feeble glow of a dim and distant sun makes me reluctant to dismiss it without further exploration of the wonders exhibited by hydrothermal vents.

We can also attack the issue of astrobiology through evidence that comes to us from space. In Morocco, Willis travels with a party that prospects for meteorites in the desert country that is considered prime hunting ground because meteorites stand out against local rock. He doesn’t find any himself, but his chapter on these ‘fallen stars’ is rich in reconsideration of Earth’s own past. For just as some meteorites help us glimpse ancient material from the formation of the Solar System, other ancient evidence comes from our landings at asteroid Ryugu and Bennu, where we can analyze chemical and mineral patterns that offer clues to the parent object’s origins.

It’s interesting to be reminded that when we find meteorites of Martian origin, we are dealing with a planet whose surface rocks are generally much older than those we find on Earth, most of which are less than 100 million years old. Mars by contrast has a surface half of which is made up of 3 billion year old rocks. Mars is the origin of famous meteorite ALH84001, briefly a news sensation given claims for possible fossils therein. Fortunately our rovers have proven themselves in the Martian environment, with Curiosity still viable after thirteen Earth years, and Perseverance after almost five. Sample return from Mars remains a goal astrobiologists dream about.

Are there connections between the Archean Earth and the Mars of today? Analyzing the stromatolite fossils in rocks of the Pilbara Craton of northwest Australia, the peripatetic Willis tells us they are 3.5 billion years old, yet evidence for what some see as cyanobacteria-like fossils can nonetheless be found here, part of continuing scientific debate. The substance of the debate is itself informative: Do we claim evidence for life only as a last resort, or do we accept a notion of what early life should look like and proceed to identify it? New analytical tools and techniques continue to reshape the argument.

Even older Earth rocks, 4 billion years old, can be found at the Acasta River north of Yellowknife in Canada’s Northwest Territories. Earth itself is now estimated to be 4.54 billion years old (meteorite evidence is useful here), but there are at least some signs that surface water, that indispensable factor in the emergence of life as we know it, may have existed earlier than we thought.

We’re way into the bleeding edge here, but there are some zircon crystals that date back to 4.4 billion years, and in a controversial article in Nature from 2001, oceans and a continental crust are argued to have existed at the 4.4 billion year mark. This is a direct challenge to the widely accepted view that the Hadean Earth was indeed the molten hell we’ve long imagined. This would have been a very early Earth with a now solid crust and significant amounts of water. Here’s Willis speculating on what a confirmation of this view would entail:

Contrary to long-standing thought, the Hadean Earth may have been ‘born wet; and experienced a long history of liquid water on its surface. Using the modern astrobiological definition of the word, Earth was habitable from the earliest of epochs. Perhaps not continuously, though, as the Solar System contained a turbulent and violent environment. Yet fleeting conditions on the early Earth may have allowed the great chemistry experiment that we call life to have got underway much earlier than previously thought.

We can think of life, as Willis notes, in terms of what defines its appearance on Earth. This would be order, metabolism and the capacity for evolving. But because we are dealing with a process and not a quantity, we’re confounded by the fact that there are no standard ‘units’ by which we can measure life. Now consider that we must gather our evidence on other worlds by, at best, samples returned to us by spacecraft as well as the data from spectroscopic analysis of distant atmospheres. We end up with the simplest of questions: What does life do? If order, metabolism and evolution are central, must they appear at the same time, and do we even know if they did this on our own ancient Earth?

Willis is canny enough not to imply that we are close to breakthrough in any area of life detection, even in the chapter on SETI, where he discusses dolphin language and the principles of cross-species communication in the context of searching the skies. I think humility is an essential requirement for a career choice in astrobiology, for we may have decades ahead of us without any confirmation of life elsewhere, Mars being the possible exception. Biosignature results from terrestrial-class exoplanets around M-dwarfs will likely offer suggestive hints, but screening them for abiotic explanations will take time.

So I think this is a cautionary tone in which to end the book, as Willis does:

…being an expert on terrestrial oceans does not necessarily make one an expert on Europan or Enceladan ones, let alone any life they might contain. However…it doesn’t make one a complete newbie either. Perhaps that reticence comes from a form of impostor syndrome, as if discovering alien life is the minimum entry fee to an exclusive club. Yet the secret to being an astrobiologist, as in all other fields of scientific research, is to apply what you do know to answer questions that truly matter – all the while remaining aware that whatever knowledge you do possess is guaranteed to be incomplete, likely misleading, and possibly even wrong. Given that the odds appear to be stacked against us, who might be brave enough to even try?

But of course trying is what astrobiologists do, moving beyond their individual fields into the mysterious realm where disciplines converge, the ground rules are uncertain, and the science of things unseen but hinted at begins to take shape. Cocconi and Morrison famously pointed out in their groundbreaking 1959 article launching the field of SETI that the odds of success were unknown, but not searching at all was the best way to guarantee that the result would be zero.

We’d love to find a signal so obviously technological and definitely interstellar that the case is proven, but as with biosignatures, what we find is at best suggestive. We may be, as some suggest, within a decade or two of some kind of confirmation, but as this new year begins, I think the story of our century in astrobiology is going to be the huge challenge of untangling ambiguous results.

https://api.follow.it/track-rss-story-click/v3/jGd80SoQARX-lNVAUO9iX2_63bikK-sP

Unless I missed one or two.

Unless I missed one or two.